Difficult relationship between IB, AP students must be addressed

February 12, 2016

I remember attending open house as a prospective Central student in eighth grade. I remember being told again and again by current students not to worry about making friends because Central was a welcoming and cohesive environment. Typical high school woes marked by unpopularity and cliques simply didn’t exist here.

For the most part I still feed that to future freshmen. As a senior, I still truly believe that Central is a remarkably accepting and mature environment for a high school. Unfortunately, the International Baccalaureate program installed in 2012 jeopardizes this atmosphere in the school.

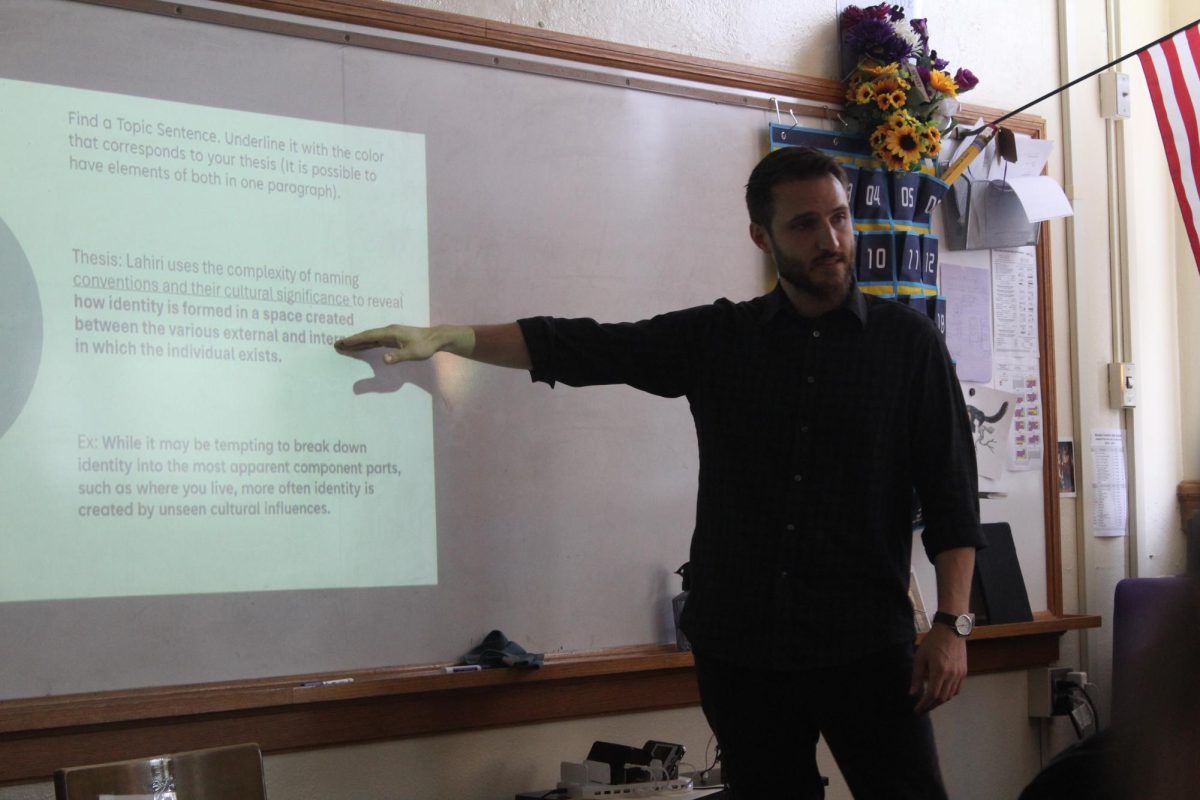

International Baccalaureate, or IB, is a separate set of courses that can be selected by students who would otherwise likely continue on the honors or Advanced Placement track. The IB Diploma Program begins in junior year and continues until graduation. Students still take classes such as English or chemistry, but are also required to take etymology courses such as “Theory of Knowledge,” as well as complete four years of foreign language. The program offers a more broad and worldly approach to learning, and attempts to connect all curriculum so that it can be understood in a more meaningful way.

Central chose to begin an IB program as a spotlight program for the school. It was meant to draw in more high-achieving students that were interested in a special curriculum outside of Advanced Placement or honors classes. In the metro area, the only other school that offers IB is Millard North, nearly 30 minutes away from Central.

Though International Baccalaureate is a quality academic program that undoubtedly provides many educational benefits for its students, it represents a separation present in Central that divides our student body. The perceived benefits given to IB students, as well as the difficult relationship between IB and AP students, causes tension, bitterness, and dissent, and, unfortunately, it is detrimental to the very morals that Central prides itself on. As an institution home to over 2,000 students from different racial, socioeconomic, religious and ideological backgrounds, we preach sentiments of acceptance and community, while the IB program currently serves only as an obstacle to these ideals.

Instead of innocently serving as an optional academic program that is no better or worse than another track, IB has transformed into something with a life of its own. Many participants have largely adopted the mentality that IB is an elite group of students in a rigorous program meant only for the best; while IB is undoubtedly difficult, and students must be willing and able to put in the work, it’s been forgotten that one may choose to opt into the program. There are no placement exams or previous intellectual requirements to fulfill. The student who chooses to follow the Advanced Placement track is no lesser in mental capacity than the student who chooses to enter IB, and vice versa. Still, the ramifications of such a belief are present in the minds of student and faculty alike.

IB students and AP students argue over who has more homework and which classes are more difficult, when, in reality, no one can truly say.

No student has been through both programs.

IB and AP students alike must agree that the programs are separate entities with different requirements and different purposes, and to compare them in terms of rigor is useless.

If this is true, the faculty must also cease giving IB students special treatment. Each month, IB students are afforded a day in the library to catch up on homework and study. AP students, similarly overwhelmed with class work, projects and papers to write, are not treated with as much sympathy. When learning opportunities arise, such as student screenings at Film Streams, IB students immediately fill the available slots.

Students can be told time and time again that they are equals, but when they are not treated as such, the effects are readily seen.

The IB program is academically sound, and certainly provides many benefits to Central. Still, the advantages of the program must be reconsidered if the moral fabric of the school is being threatened. We have forgotten what matters to us, or, at least, what students have been taught that matters; Central is a community, not a school with separate groups of students at war with one another.

Mark Pointer • Mar 11, 2016 at 3:46 pm

The sense of entitlement and squabbly complaints of this generation. Smh

Tom • Feb 13, 2016 at 9:44 pm

Millard North is 20 minutes from Central, not 30.

Anon • Feb 13, 2016 at 3:17 pm

This is ridiculous. Never was there a war between those groups of students at school. Relax a little. Its not that serious.

Central Alumni • Feb 12, 2016 at 3:46 pm

First of all let’s get this straight. You say that nobody can do both programs, then why did you have the opportunity to talk about both programs. You can’t see the perspective of being an IB student without even being in the program. You are the one that is creating this “war” if not creating, then helping it and making it grow. Many of the kids really don’t mind that students are taking the IB program and you are making it seem like IB students are pretentious. If AP kids or non AP kids are saying false accusations then IB kids aren’t going to sit there and listen, they are going to defend themselves. Both programs are equally great and you being the editor in chief should have realized that there isn’t a division or war or bitterness. If someone talks something that is wrong about you, you need to let them know the truth. And this whole article is full of lies that were made by ignorance. IB kids are not pretentious, they are not ignorant, same with AP kids, but you writing this article and being a high school student was wrong. As a good writer you need to value both perspectives, why are you judging the IB program when you haven’t even been in it through the whole process? Who gave you the right to speak for the IB program? I am very disappointed with how you tried to address an issue when you have your own bias influencing your word choice. Think again and instead ask kids that are actually from the IB program instead of you assuming things. Thank you.

HB • Feb 19, 2016 at 12:22 pm

Of course there is bias. It is an EDITORIAL, not a news story. Journalists are supposed to have bias in opinion pieces.

KT • Feb 19, 2016 at 1:26 pm

I never attempted to portray the perspective of an IB student. As an AP student and a Central student, I am more than qualified to give my opinion on the effect that IB has on my school and the opportunities available to me and my peers. I am entitled to share how IB students come across to me. It’s an opinion piece. There are no inaccuracies or false accusations. Reread it, and consider the true meaning and purpose of the article.