As Central adjusts to LB 140, which bans student use of personal electronic communication devices on school grounds, one local high school has been banning phone use for over a year now.

Benson High School became the first OPS school to adopt a phone ban in the 2024-25 school year, and students and staff report promising results.

“Last year, I looked at my grades from the previous year when we didn’t have the cell phone policy. And I saw that my passing rate had doubled. And I would say this year my passing rate is even higher. I’ve also had fewer students cheat on exams. I’ve seen fewer fights in our hallway. I used to break up a fight outside of my classroom once a week, and I haven’t even seen a fight this school year,” Benson journalism teacher Justine Garman said.

Before the ban, Benson did not have an official phone policy in place. Managing student cellphone use was left to the discretion of individual teachers. Garman required students to keep their devices stored but was unable to assign consequences when they failed to comply.

Like Central, Benson allows students to access their devices during passing periods and lunch. Central students are allowed multiple reminders before security is called, while Benson students have their devices confiscated immediately if they ignore the single warning before class.

Benson senior Jack Agbeve was concerned when Benson announced its plans for a cellphone ban. “I was a bit scared for the other students because I know a lot of people are super dependent on their phones,” Agbeve said.

More than a year after the rollout, students are still facing consequences for using their phones during instructional time.

“They just feel like they need to have it with them because they get bored or something,” Agebeve said. He pointed to a fight he witnessed between some Benson football players and their coach after they refused to put their phones away for an hour.

Garman has encountered similar challenges enforcing the ban in her classroom. Some students have tried to remove their phones from the designated “phone hotel” during class, and others have refused to place them there altogether.

She stresses the importance of being firm when addressing these behaviors. “Once they find out I don’t play like that, then I don’t have any issues,” Garman said.

While there was some difficulty transitioning into the ban, students now understand the expectations. Garman has only had to call for an administrator once this year. Ensuring the consistent enforcement of a total phone ban is difficult, especially at a school with a student body as Central’s, but Garman notes that “teachers who support other teachers will enforce this.”

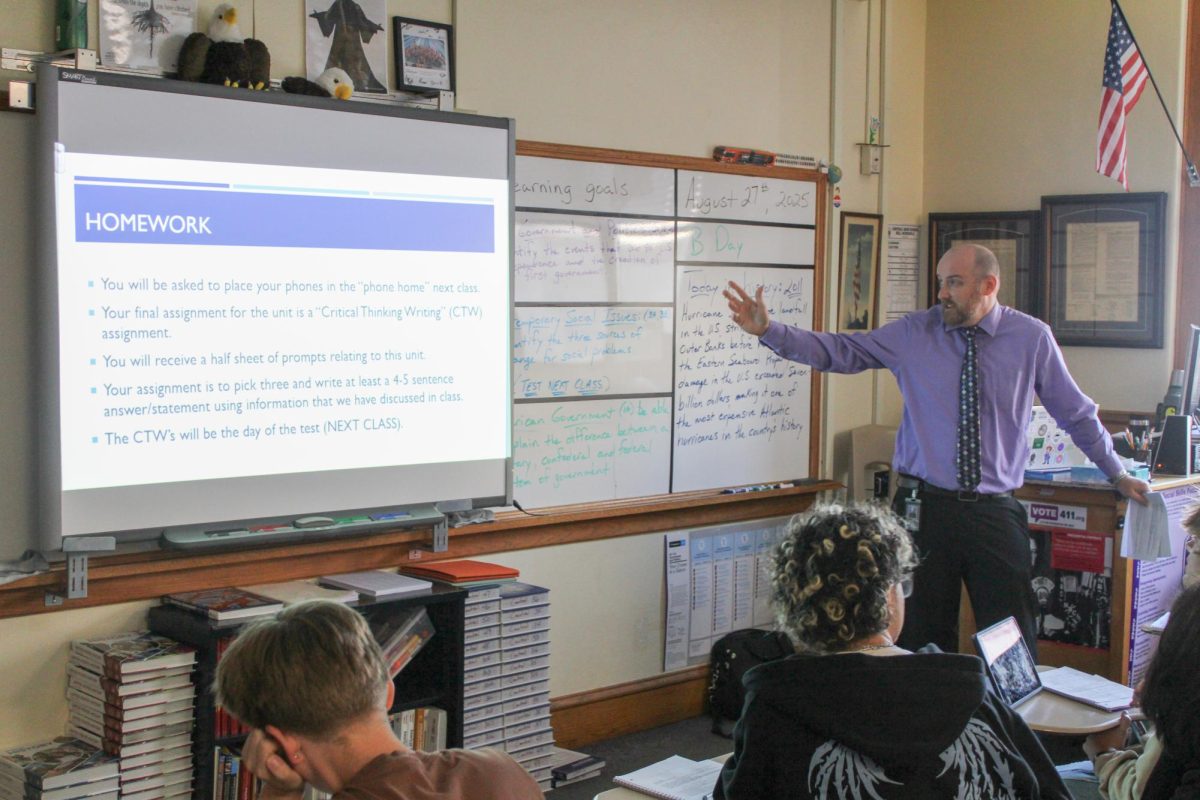

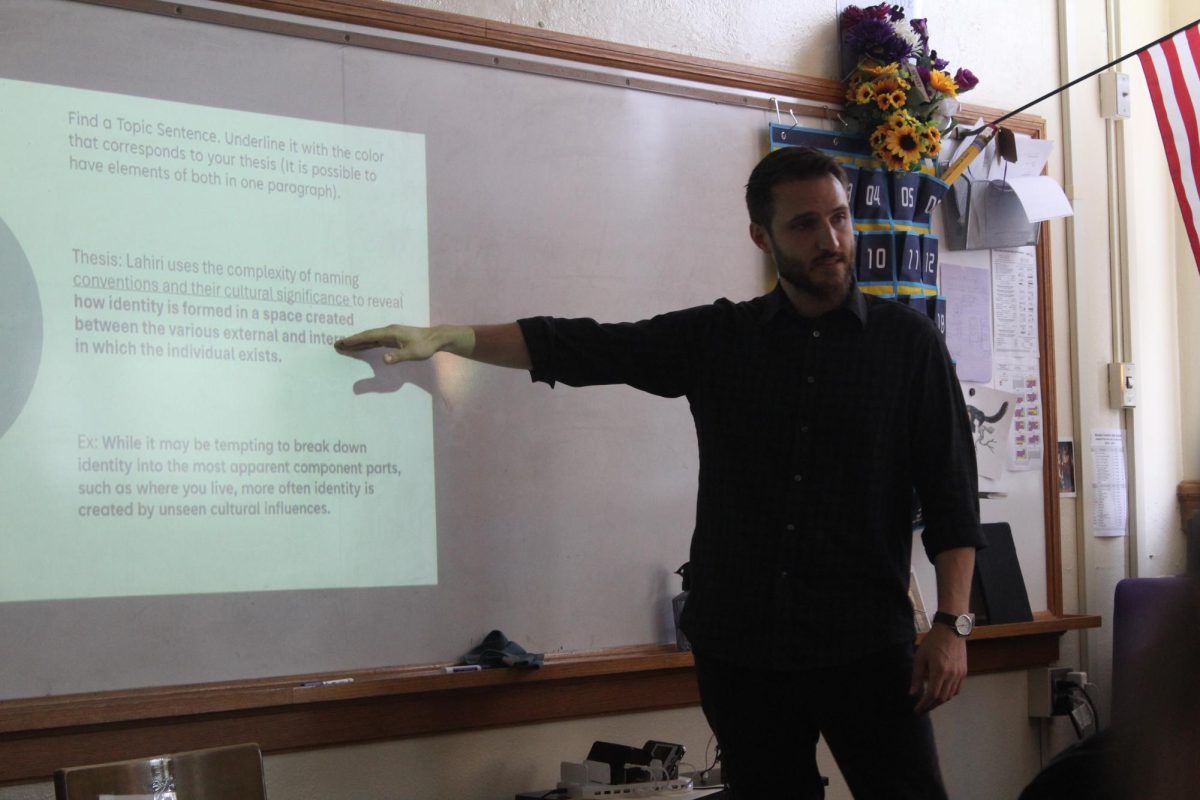

The phone ban had little impact on Central social studies teacher Scott Wilson, whose classroom policy already required students to put their devices away. Nevertheless, he welcomed the idea of a standardized policy across all classrooms.

Although adjustment is an ongoing process, Wilson has seen an overall improvement in behavior.

“I think teachers have been advocating for this for a while, and we think for the most part it’s been a plus. One of the big upshots is that students are actually talking to one another now,” Wilson said.

Wilson observed an increase in restless behavior reminiscent of his pre-computer years of teaching since the ban.

“I tend to be a person who thinks that young people are pretty similar across eras. Phones have been the one thing that have really maybe separated generations, from the beginning of my career to now,” he said.

Central social studies teacher Casey Denton has noticed fewer complaints from teachers about phones since the ban.

Unlike Garman and Wilson, Denton never felt the need for a standardized phone policy. “I didn’t have a huge issue with phones. There were kids that were on them, but it was never something that caused a lot of issues in my class. And a lot of kids, at least in sociology, were using them in lieu of iPads,” Denton said.

Additionally, she hasn’t observed any significant changes in student behavior. In fact, she was pleasantly surprised by the lack of behavioral issues and arguments she has experienced.

“I think that the kids that were always super invested in school are still super invested in school, and the kids that were not are still maybe struggling in their levels of investment,” Denton said.

Agbeve echoed this sentiment, adding that even students with moderate levels of investment either fell behind or rose to meet expectations. He noted that middle schools have phone bans that help students develop a greater tolerance for keeping their phones away. As they enter high school, it becomes easier for teachers to enforce a ban.

Benson senior Rakim Hayes attended a middle school with a much stricter phone policy than Benson’s. Transitioning into high school was a challenge for many of his peers as there was no phone policy in place. According to Hayes, many students dropped in performance as a result.

He views the ban as a good compromise between students and staff.

“I feel like the phone policy at Benson is pretty balanced, and it has worked in my circumstances,” Hayes said.

“The phone policy wasn’t a perfect overnight fix because students are always going to be on their phones no matter what, but it definitely quelled some of the struggles I saw in my freshman year,” Hayes said.