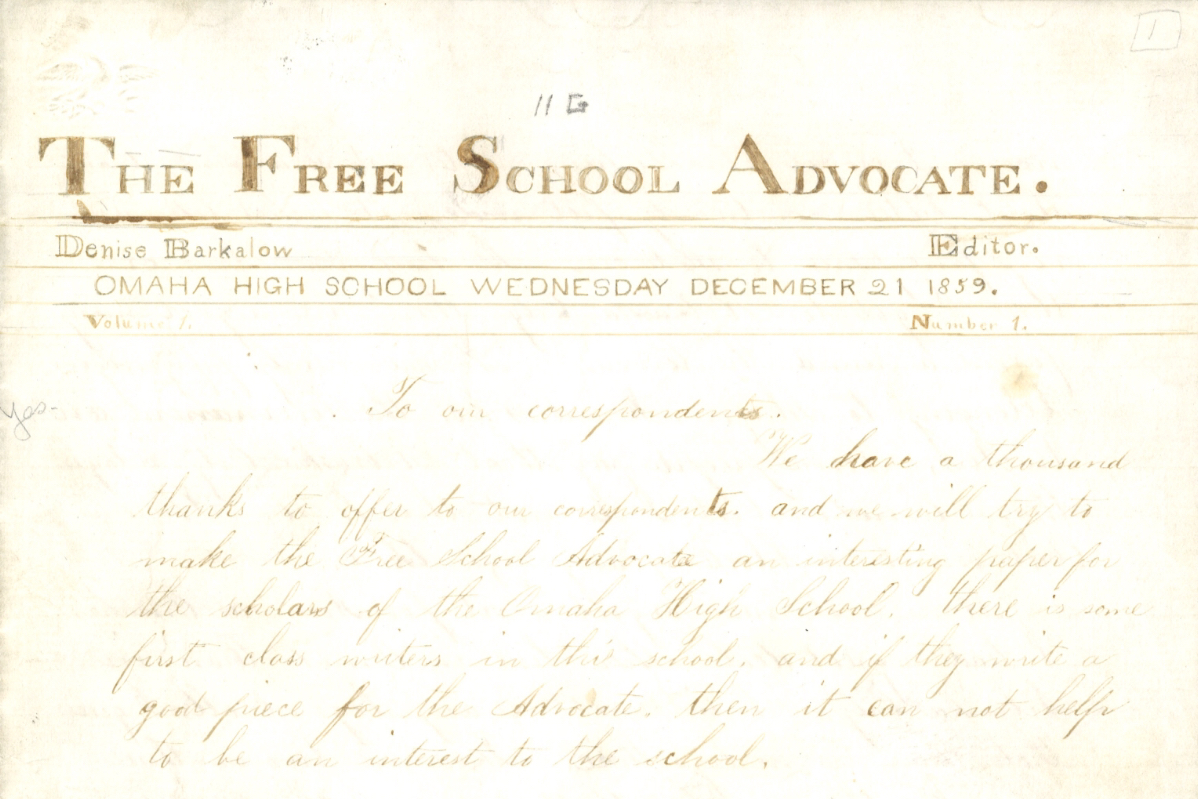

Asian-American students represented in honors classes due to parenting

February 19, 2016

Freshman year I took an honors class that I loved that was taught by a teacher of a different skin color than me. I remember vividly the way I felt when one day, my teacher asked if any of us had ever been to a certain restaurant—a small restaurant, the name of which isn’t important, but located deep in a neighborhood of North Omaha—and only two people, other than myself, raised their hands. The two who raised their hands were both African-American, and it was then when I realized we were the only three students of minority in the class.

I am proud to attend Central for many reasons, but one of these reasons has always been its diversity. According to the Nebraska Department of Education’s online data for the 2014-15 school year, 25 percent of Central’s population was black or African-American and 23 percent was Hispanic.

This trumps fellow OPS school Burke High, which had a population of 21 percent black and 15 percent Hispanic. Moreover, it completely outdoes Millard West and Millard North, both of which had combined black and Hispanic populations of less than 10 percent.

But even though the numbers boast Central’s diverse school population, the memory of that freshman year honors class has always existed in the back of my mind.

Now I’m a junior, and every class on my schedule is AP or honors. It’s hard not to question why I see so few faces of color in my classes. Central certainly doesn’t deny students of color entry into AP or honors classes, but the classrooms remain segregated.

Even walking into a regular-level class reveals to me an entirely different setting and a group of students who look nothing like the people in the classes I’m in. It’s almost like there’s a whole different school simultaneously exisiting in the same building as my own.

I really do feel overwhelmed by the number of my peers who are white. But can I even claim to be minority? I’m only 50 percent Vietnamese, and even then, Asian-Americans seem to be the exception to the minorities-achieve-less-than-white-people rule.

But why is that? Why are the non-honors classes of Central filled with African- and Hispanic-Americans while the Asian-Americans, small in number, sit in the classes amongst majority-white peers? And why does the stereotypical Ivy League graduate sport an East Asian’s complexion with a perfect ACT composite?

I’m blaming it on the parents.

A couple of weeks ago, my brother was grounded because he received a score of a B- on a homework assignment. He’s in 6th grade, and the assignment didn’t even count towards his grade in the class. But my parents are tiger parents, and he should have seen it coming.

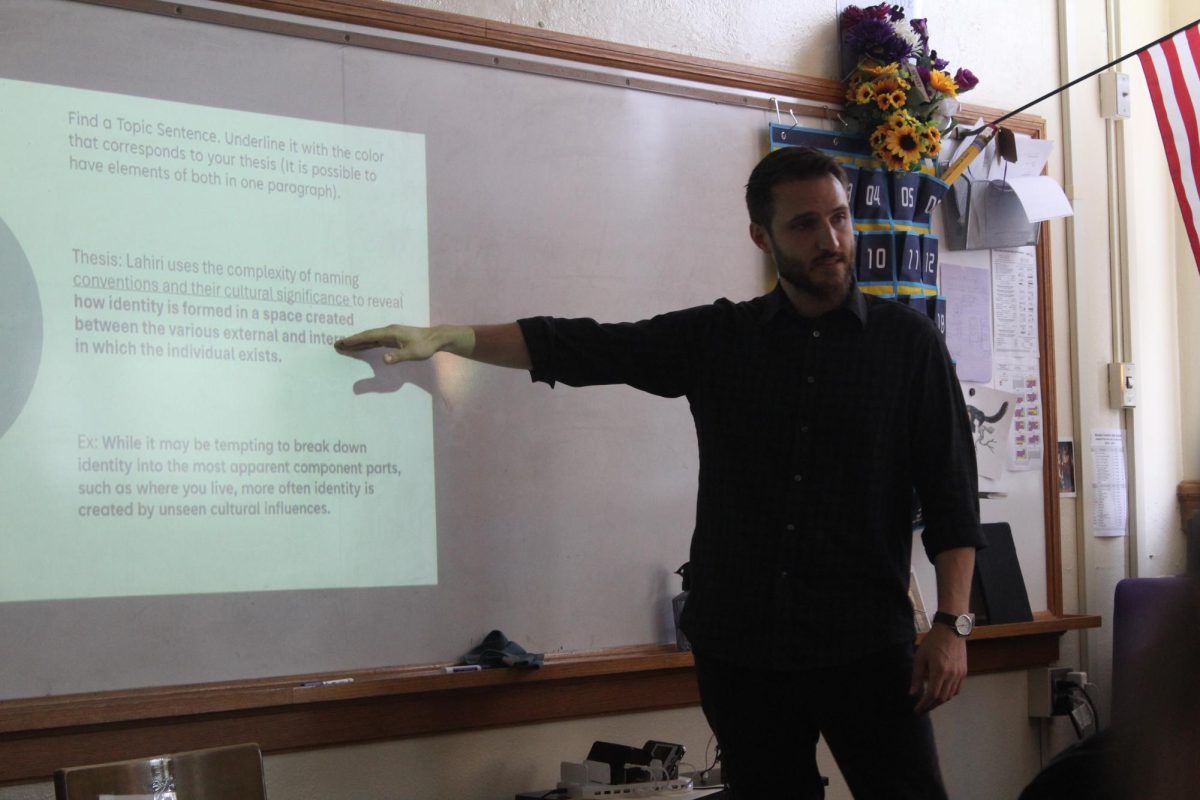

“Tiger parent” was a term introduced by Amy Chua in her 2011 book entitled “Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother.” In “Battle,” Chua compares her Chinese parenting style with those of “Western” mothers. Chua’s main argument is that Western parents are overly-concerned with their children’s self esteem, while Chinese parents assume their children are strong enough to endure harsh criticism and exceedingly high expectations. Since then, magazines such as TIME and Wall Street Journal have published subsequent articles considering the effectiveness of the Chinese-style upbringing and adopting the “tiger parent” label.

The term caught on, and “tiger parent” is now an expression casually thrown around to describe a parent with extremely strict tendencies. (The phrase “helicopter parent” is used in the same way.)

So, my parents are tiger parents. But this isn’t meant to be a hate session where I complain about my parents’ expectations of me. I can’t deny that sometimes it’s irritating when an A- doesn’t satisfy my parents. My brothers could testify that the forced cello practicing sessions and one-hour-a-day-video-game limits get old.

But I love my mother, and she and my father have fostered me into the successful 16-year-old Asian girl that I am.

The 16-year-old Asian girl who is the only one of her kind in her Calculus class.

TIME magazine published an article in May 2014 entitled “The Tiger Mom Effect is Real.” The article stated that data opposed claims that social and economic status caused a gap in academic success; instead, it was largely attributed to work ethic and upbringing. TIME said that in a study of 5200 students, the majority of white students considered intellect something one is born with, while the Asian students attributed it to hard work.

Tiger parent upbringing forcefully encourages hard work and nothing but. Because of this, I’m less scared to give a speech in front of a thousand strangers than to my own two parents, and I would much rather let my friends tear my papers apart than let my father, who was an English professor, proofread them.

My parents’ expectations of me are ridiculous, but my own expectations of myself are even worse. An A- here and there will fly with my mother, but I’ll be disappointed. Anything less than perfection indicates to me that I have to work even harder. Did my tiger parents breed this unreleastic expectation of flawlessness I have for myself? Probably. I’m going to toot my own horn and say I’m largely responsible for my achievements, but my parents have undoubtedly helped.

The freshman year me that sat in her honors class next to rows and rows of white peers didn’t quite understand her priveleges. I’m proud of the academic advantage I have thanks to my parents. And even though it can’t be assumed that all Asian-American parents are tiger parents, I suspect it’s a large reason for Asian-Americans’ successes.

But while this might solve the mystery of why Asian-Americans seem to achieve academically on the same level as their white friends, it leaves a lot in the dark about other minority groups.

Someday I’d like to take an AP class with friends who are not just whites but also blacks, Hispanics, Native Americans or fellow Asians.

But for now, thanks Mom.