District sought multiple views before field testing different grading scale

Another iteration of a grading scale will soon be implemented into the district, in hopes that the newest scale will fix the flaws that have been reported. A grading committee composed of twenty members that include teachers, administration and OPS staff have come up with a new grading scale and have been field testing it in certain subjects in both secondary and elementary classes. Those subjects include 4th grade mathematics, 7th grade social Studies, 8th grade English and physical science, and high schools subjects such as algebra, English, world history and physical science. These courses were chosen because they represent a wide range of subjects and would affect a large number of students.

The main catalyst behind the changing of the grading scale was the trend of reports in feedback from teachers that a student’s understanding of a subject was not adequately reflected under the current grading scale. Students could do below basic work and still pass a class and earn a credit, and others could do proficient work and have one assignment be advanced and earn an A. That was of concern for the grading committee, which then sought out a solution to fix the underlying problem.

The process began with considering that a student could do below basic work and still pass a class. So, that became the cutoff for the grade of an F, between a zero and a one. Then, the last four grades left were split into equal increments, which now made earning an A just a little bit harder. This new grading scale could provide a solution to inaccurate grade inflation, according to Tom Wagner, data administrator for Omaha Central and one of the members of the grading committee. “We had 750 kids earn Purple Feather [last year]. That’s a great story, don’t get me wrong, and it’s great to tout and brag about because I think Central is a great school with awesome academics,” Wagner said. “But is it accurate to say the equivalent of a class and a half has a 3.5 cumulative GPA or better?”

While Wagner is administrator, he has come to the conclusions about the grading scale through years of teachers approaching him with examples of students that are barely above the cutoff for passing in the current grading scale. That is due to countless students not turning in assignments yet earning just enough on some assignments to earn a credit.

He ran a report on how many credits were earned by students at Central that had between a 0.76 and a 1.00 in a class during a particular grading period and found that over 600 credits were earned with grades within that range. Then, he ran a missing assignment report on those students and found enough missing assignments to fill 700 pages. That does not take into account the other six OPS high schools.

That was a blaring problem for the grading committee and for the district that needed to be urgently solved. However, there was still some trepidation from some of the committee members in choosing to immediately implement the new scale, similar to the previous times that the district has implemented new grading scales fairly quickly. That is why the majority of the committee voted to field test the scale in some classes.

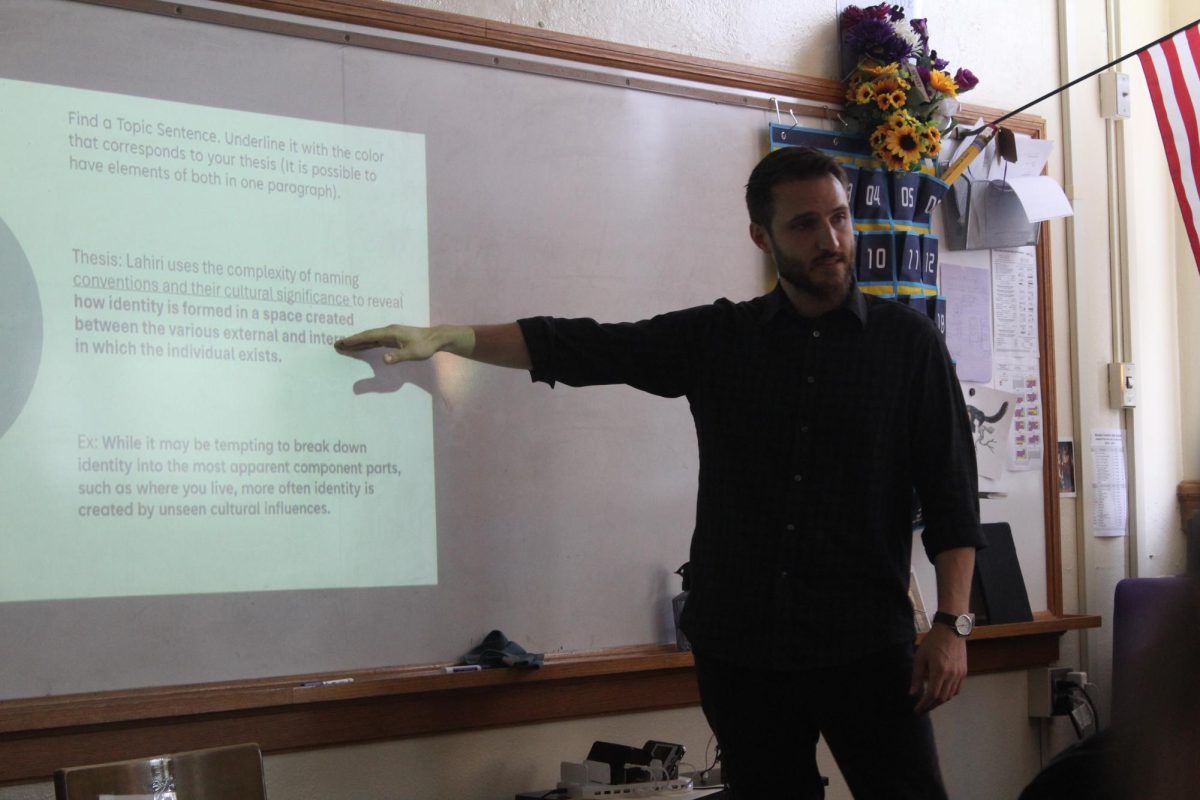

There was a minority however; not only was Wagner in that minority but also Marcella Mahoney, English teacher at Omaha Central and another member of the grading committee. She teaches both Honors English for freshman and AP Language and Composition for juniors, and has taught sophomores and seniors previously. “I wanted to have [the new grading scale] applied to all classes and all grades this year,” Mahoney said. “I believe that if the bar is this high, a kid will jump that high to hurdle the bar to get the grade that they want.”

Both Wagner and Mahoney respect the decision of the majority to field test the scale in order to make sure the district gets this scale right. That was a main focal point for the committee according to Anthony Clark-Kaczmarek, director of Curriculum Instruction and Assessment for the district. “I think it’s important that any scale that we have demonstrate the understanding that students have of the content that is being presented,” Clark-Kaczmarek said. “The grading scale is a representation of what students know and understand. We want to make sure that is an accurate reflection.”

Regardless of when the grading scale is being fully implemented, teachers at Central are happy with it, according to Wagner. He also likes the added rigor the scale brings and the motivation for students to try just a little bit harder. “I like that you have to work a little bit harder to get that credit,” Wagner said. “A credit from Central High School or from any school in OPS needs to be worth something.”

Some other ideas were thrown around by the committee to improve the grading scale, but more in a hypothetical sense. They considered eliminating the D altogether, adding a 1.5 to the proficiency scale, changing the values of summative and formative assessments and more thought-provoking ideas. However, those ideas will not be part of the changes, they were simply thoughts the committee had.

Other factors play into the changes to the grading scale. The actual grades that are being awarded have not changed; just the scale in which they are based upon. Added abilities for teachers to weight assignments with a multiplier of two, three or four can make certain assignments count more towards a final grade. Teachers now are allowed more freedom to use their professional judgement to give redos, accepting late work and in determining final grades for students. There were also clarifications to the term “zero” and “missing,” meaning that “missing” actually means an assignment has not been turned in, even though it may calculate as a zero. “Zero” means that a student does not show any evidence of understanding of a given topic.

The changes on the “blanket” policy for late work and redos were welcomed changes for Mahoney. In her teaching experience, she has had students get back assignments and use her as an “editor” of sorts to earn higher grades, whether they had an F or an A on a particular assignment. “There’s just not time in any teacher’s life to have an endless cycle of redos,” Mahoney said. “What teachers are given now is their professional judgement to decide when a redo is the best option and when accepting late work is the best option. I appreciate that the new system is letting the professionals use their training, their judgement and their relationship with the kid to be able to make the best decision for any student at any given point in time.”

The overall agreement between teachers and administrators across the district is that the new grading scale is a positive solution to the inaccuracies in the current grading scale. “Right now, the changes aren’t terribly drastic,” Wagner said. “This isn’t perfect but I think it’s a step in the right direction.” Mahoney hopes that this is the last time the public and the learning community will have to have a conversation about the grading system. “While [the committee is] open to revision, we think that this is going to work out,” Mahoney said. “Hopefully this is the last revision to the day to day grading practices, but I’m also enough of a realist to know that things evolve, and new situations come up.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Omaha Central High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Alec is a senior at Omaha Central, and writes for the fourth year on the staff of The Register. He has written on a variety of topics during his time in...