Broadcast crew brings Central athletics to wider audiences

February 9, 2022

When Dr. Keith Bigsby was in his final year as principal, he wanted to improve the fan experience in the gym lobby at Eagle basketball games. Within less than a year, this dream led to the creation of Central’s first broadcast crew.

Bigsby’s original goal was to boost sales at the concessions stand in the gym lobby by adding a debit and credit card payment system and televisions. The card reader—the first of its kind in the district—was a response to the fact that the student body was beginning to carry debit or credit cards more often than they would carry cash. The televisions were a response to the fact that fans were less likely to go get concessions during the game, for fear of missing part of the action.

“That was the premise of our first attempt to go do some live casting,” Bigsby said. “We were really doing it in-house, into the gym lobby, so we could sell people stuff.”

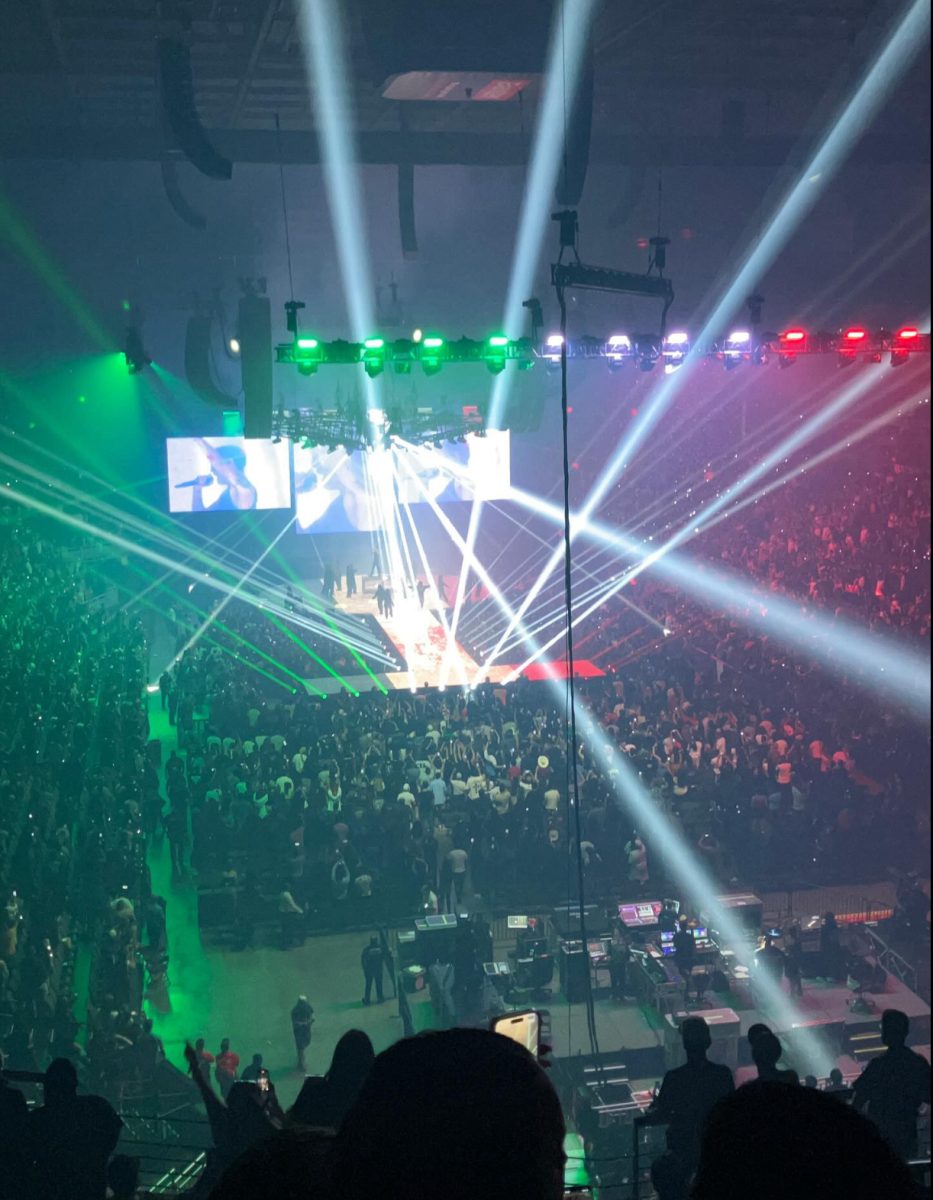

From there, Bigsby went to the Central High Foundation and asked for money to pay for a good camera and a contract with Striv.TV, an online streaming service that helps high schools broadcast their games. This made Central the first school in the city to sign up with Striv, which is now used at about 158 schools in the state.

Bigsby started with basketball. He convinced two students to join the broadcast crew, and they went to work with a single camera, a computer, and a microphone, instead of the headsets they have now.

“We felt like we were pretty big time, until we got down to state, and we saw Kearney,” Bigsby said. “They had a three-camera set up, they were running sound boards, and they were watching the video on screens. At that point, I said, ‘My goodness. We’re ahead of the curve in Omaha, but we’re behind the curve in the state of Nebraska.’”

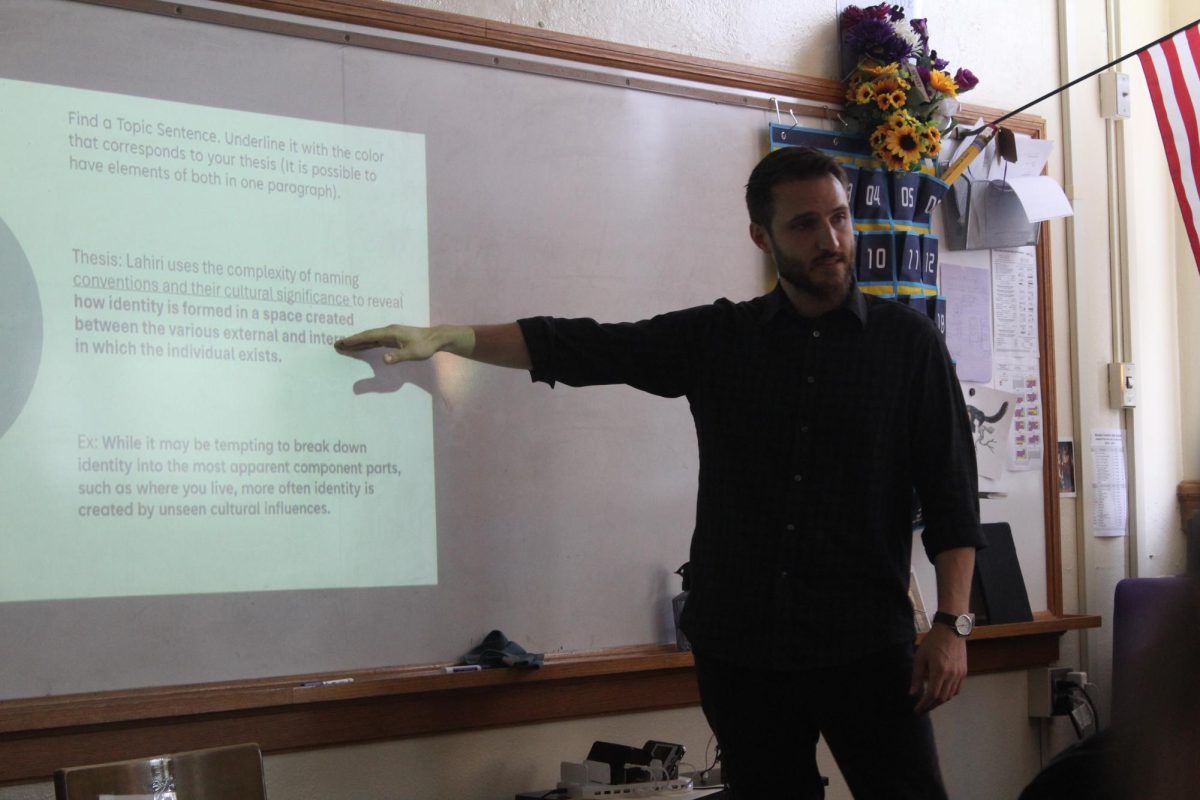

Some of the small towns across the state had students that took broadcasting as a class, not just an extracurricular activity. This put those schools far ahead of Central at the time. The people who changed this for Central’s broadcast were the Register editor at the time, Alec Rome, and Central parent and media specialist Sean Weide. They both introduced new ideas about how the broadcast should be run.

“The one thing about me is I’m not going to tell anyone is ‘no,’” Bigsby said. “If you’ve got a good idea, let’s go play.”

Before long, the broadcast had grown to cover not just basketball, but also football, wrestling, and soccer. It has even branched out from sporting events to cover other school events, including the Hall of Fame induction ceremony, senior recognition night, and theater productions. The Foundation has continued to buy equipment for the broadcast crew, as well as pay a small stipend to the students who are a part of the crew.

Now, the broadcast attracts around five hundred to a thousand viewers for an average game, and anywhere from two to five thousand for a highly anticipated game. The gym still fills up for each game, which silenced the main argument against live casting, which was that it would hurt ticket sales.

“What we discovered was that you’ve got people from Kansas City, Chicago, and Los Angeles, all over the country watching this stuff,” Bigsby said. “And the interesting thing is that a lot of those are alumni, but a lot of them are coaches. That’s a compliment to our crew, that we make a good enough product that they’ll watch it.”

Last year, with no fans allowed in the gym, viewership grew all the way up to fifteen hundred per game, peaking near five thousand when Central faced Millard North. This brought some opposing fans to the broadcast and with them, some discontent.

“What people don’t understand about us, especially if you’re the opposing squad, is that I’m not for your team,” Bigsby said. “We’ll be nice, but I’m not going to give you the love that I’m going to give the Eagles. That was one of the biggest complaints, that we’re not neutral. Did you not see that this is the Eagle broadcast network?”

Bigsby also said that this has to do, on some level, with telling the truth about the opposing team.

“We’re not going to sit there and say, just because you’re Millard North and you’ve got some really good players, that we’re afraid of you,” he said. “If they’re not playing well, I’m going to let you know. There’s an honest dialogue that’s going on, and I think that’s important.”

Looking forward, Bigsby wants to expand to cover more sports, including underclass games and cross country meets. He’s talked about covering almost anything that goes on at Central, but there are barriers that the broadcast crew will have to overcome before they can do that.

“There’s a lot of things that go on in this school that you just can’t get to, like the math contest or the acapella choir performances,” Bigsby said. “There’s just so much that goes on, and the real question is how do we capture that, and that comes back to the fact that I have to have kids and I have to have equipment in order to do it.”

In the long-term, Bigsby believes that the new pathways curriculum will allow the broadcast program to continue to grow at Central, so long as he can get teachers and students interested in participating and willing to put in the work.

“If we get the right classes established in the pathway,” Bigsby said, “there’s nothing stopping students from learning how to do the camera, learning how to do the production, and learning how to do the directing, and then doing the social media element, too, giving kids the opportunity to put together a good product.”