Foreign language education in flux

Students and educators in Nebraska’s language classes are grappling with the implications of the Covid pandemic and reduced funding for Nebraska’s world language program.

Speaking instruction and conversational activities saw a reduction following virtual learning and social distancing, according to teachers and foreign language experts. Physical separation, whether virtually or in the classroom, limited students’ interactions and comfortability with speaking to each other.

“There’s a very negative impact of Covid on students because this is a language. It’s about communication,” said Chrystal (Xianquan) Liu, the world languages specialist at the Nebraska Department of Education.

Cecilia Tocaimaza-Hatch, the department chair of Foreign Languages and Literature at the University of Nebraska at Omaha, noticed that students continuing their language education from high school should’ve been more prepared to speak confidently in their target language.

“Sometimes we feel that they have perhaps taken many classes in high school, but perhaps they have not been able to interact in the target language in some situations that would push them to produce language more naturally,” Tocaimaza-Hatch said.

After taking three years of French, senior Mayra Grima-Topete said that speaking more of the language in class could have helped her better achieve fluency. Grima-Topete said she would be able to hold a small conversation in French.

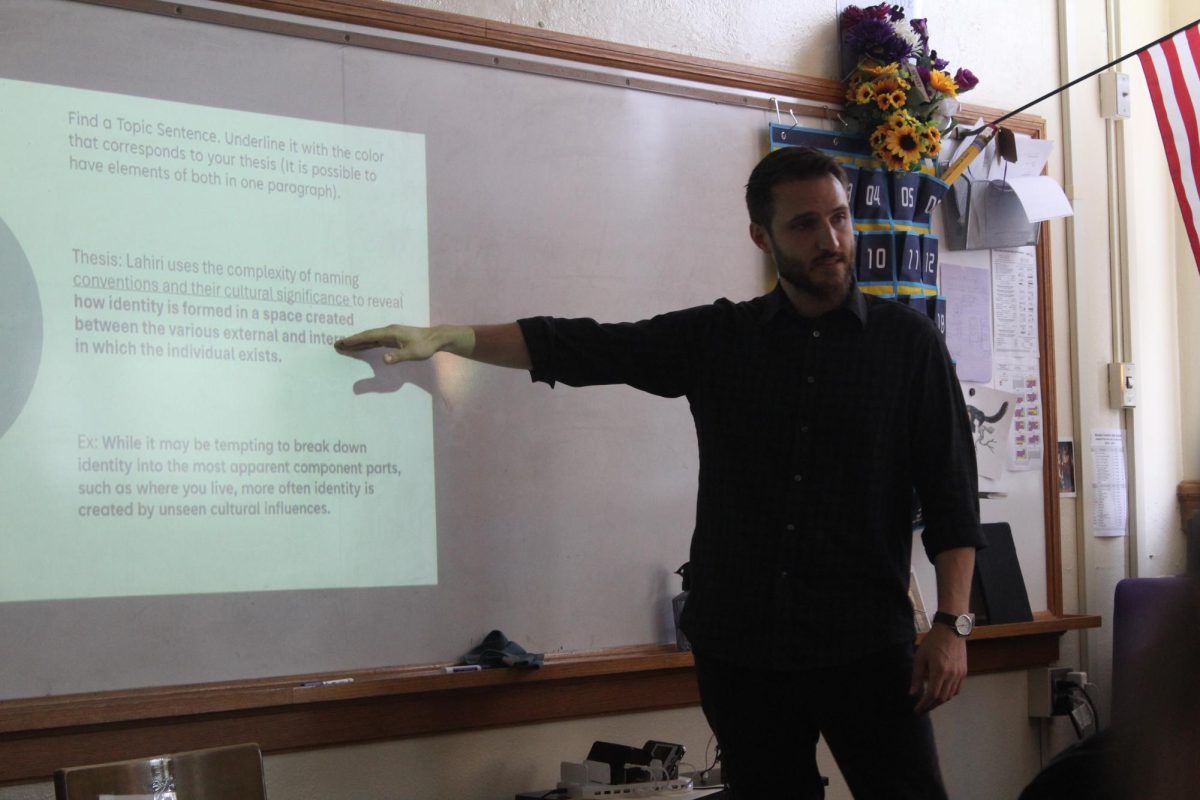

Erica Meyer, the language department head at Central, said that getting students to speak with each other is difficult but that students are more comfortable with each other by their third year of instruction.

Elana Elder, a 2022 Central graduate who took International Baccalaureate (IB) French, said, “Definitely in IB classes, it was very centered around speaking and just becoming more fluent in the language because that was part of the testing. And I think because of that, I feel a lot more comfortable with French than I did before.”

Meyer said having students ask for bathroom passes or other needs in the target language could be a measure to encourage more speaking in the classroom.

However, Tocaimaza-Hatch believes that a beneficial aspect of the world language program is the experience of language learning in high school. Meyer also said that the use of the target language in teacher instruction is positive for Nebraska’s language learning.

“I think a lot of our teachers do a really good job of speaking as much of the target language as possible,” Meyer said.

According to Tocaimaza-Hatch, students who took a language in high school are “far more prepared” for college-level language classes because they already know themselves and their language learning abilities.

Liu and Tocaimaza-Hatch said that language classes in OPS and school districts across the state are being reduced or completely cut as school budgets cannot support them. Language programs were also discontinued when some schools’ sole teachers of a language resigned due to COVID-related issues or wanting to leave the teaching profession; Central’s Latin program was discontinued last year when the Latin teacher resigned and could not be replaced.

“I have to say, I’m very frustrated [about cutting language programs],” Liu said. “I’m trying to advocate for world language education. I mean, more like raise the public awareness about the benefit of language learning.”

Liu also said that certifying world language teachers in Nebraska is challenging compared to becoming certified in other states. And for teachers coming from other countries to teach in the US, “most likely they will choose another state because in other states, getting certified is not such a challenge.”

“We have a severe world language shortage in Nebraska,” Liu said.

When schools have world language teachers and programs, Liu said that teachers need to promote more of Nebraska’s language learning opportunities, such as the Seal of Biliteracy. According to Liu, many students are qualified but unaware of the opportunity to earn the state’s award for attaining proficiency in at least two languages.

“The problem is not all schools are doing it, not all teachers are aware that [of] its existence,” Liu said.

Everyone interviewed said that starting language learning younger is better, but some said that implementing language classes for younger grades could prove difficult with budget cuts and teacher shortages.

“I think it will be really cool if, in the future, public schools also started teaching languages younger, but that would also require having teachers for those ages which is kind of already an issue in the high school and middle school,” Elder said.

Liu and Tocaimaza-Hatch both cited before puberty as the easiest time for someone to learn a second language, with Liu giving the specific ages of 6 to 11. However, both individuals said that language learning is possible at an older age and is affected by factors such as personality and interaction with native speakers.

“It will depend on the student and what they do with their opportunities,” Tocaimaza-Hatch said.

Meyer said that when OPS had more language classes in middle school, it was “better.” Liu said that she “really likes” the Spanish Dual Language program in OPS because “it prepares students.”

Besides a lack of funding, not having a cultural emphasis on learning foreign languages was also cited by Tocaimaza-Hatch as a reason for starting language classes in high school. Tocaimaza-Hatch said that, with the emergence of English as a global language, Americans have stopped valuing bilingualism or multilingualism.

According to the Pew Research Center, in 2018, 20% of students in kindergarten to 12th grade studied a foreign language, while the median percentage for school-age European students was 92%.

Meyer said the US’s language fluency compared to the rest of the world is “horrible” and that “we’re way behind.” “It’s almost embarrassing as Americans. Everywhere we go, everybody’s expected to speak English for us, and Americans expect it.”

Tocaimaza-Hatch said the American value of monolingualism also extends to the treatment of heritage speakers of other languages in the US. Immigrants, especially Spanish-speaking immigrants, are expected to assimilate and learn English, sometimes at the expense of their first language.

“That’s because the US, like I was saying before, doesn’t really have a system for us to maintain those languages,” Tocaimaza-Hatch said. “Languages are learned or lost because the society assigns a value to it.”

For Spanish-speaking students, Tocaimaza-Hatch finds that there is often a double standard between them and monolingual students learning a second language; students learning a second language are given more support than heritage speakers.

“I think that often, the bilingualism that these students come with is seen as a problem and less as an asset,” Tocaimaza-Hatch said. “There’s never much of an investment in helping that individual maintain their home language and be bilingual. The focus is only always on, ‘you gotta learn English.’”

Tocaimaza-Hatch said teachers may have some of those attitudes or may not know how to work with heritage speakers.

“There are specific goals that we need to follow as teachers when it comes with heritage speakers. And the number one of them is giving them confidence for their language,” Tocaimaza-Hatch said.

Underfunding and a lack of teachers affect the Spanish for Spanish-speakers program as well, but OPS has a lot more emphasis on the program than other districts, according to Tocaimaza-Hatch.

Francisco Juarez Palomo, a Spanish for Spanish-speakers teacher at Central, said that he thinks the program is doing a good job to help heritage Spanish-speakers.

Juarez Palomo said that he has asked the district to create a new Spanish for Spanish-speakers class specifically for students who can speak Spanish but cannot write in Spanish. It would be called Spanish for Spanish-speakers 0.

Samantha Lopez-Vazquez, a Central graduate now attending Northeast Community College, said the Spanish for Spanish-speakers program helped her with her writing in Spanish. She is now able to text her family members and husband without having to use a lot of Google Translate.

“In my degree, I don’t need a language but if I would’ve, it [Spanish for Spanish-speakers] would’ve been a lot of help,” Lopez-Vazquez said.

“Learning a language opens new windows into how other people live life. And so when we don’t have that, our windows are closed. And no amount of Google Translate will make up for us being able to experience that firsthand,” Tocaimaza-Hatch said.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Omaha Central High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Hi, my name is Fiona Bryant (she/her) and I'm the Managing Editor! This is my second year on staff and I'm a senior. A fun fact about me is that every...