Teachers leaving Central

Departing teachers share their stories and their reasons for leaving the school

Thirty-seven staff members will be leaving Central High School at the end of the current school year, representing the largest exodus of staff from the school in the 21st century thus far. Of the 37 teachers leaving, three are transferring to another OPS school, six are retiring, and 28 resigned. The Register reached out to many of the departing educators, inviting them to tell their stories and explain the reasons behind their departures. In the end, 22 staff members agreed to be interviewed. Some educators requested to remain anonymous, citing personal and professional fears about sharing their experiences openly.

For some teachers, the decision to leave was made solely for personal reasons.

“I absolutely love Central and I wouldn’t want to be anywhere else in the public school setting,” said Jenna Saraka, who accepted a position at Mercy High School after teaching math at Central for five years. “I’ve said it’s either Central or go to a parochial school or don’t teach at all cause I love Central and I do feel at home here but I think it’s just time for a change.”

“Really since I started working here, I’ve been trying to get out to Elkhorn, because that’s where me and my wife live,” resource teacher Andrew Thompson said. “It’s just that it’s gonna be more convenient.”

Along similar lines, Evan Block, one of the many educators leaving the special education department, reflected on his decision, saying, “One of the motivating factors for me to interview at the new school was my wedding in the spring. My fiancé is also a teacher and we live out in Elkhorn. Westview High School is on 156th and Ida, which is much closer to where we live so it’d be a lot more convenient with us living out there and potentially starting a family.”

The new teaching opportunities at Buena Vista and Westview, the first two new schools OPS is opening in over 50 years, were commonly cited as reasons for leaving.

“It was a logical next step,” said Dean of Students Eric Behrens, who is leaving Central after 18 years to be the athletic director at Omaha Westview High School. “This is a building that has a lot of meaning for me, I have a lot of history here. If it wasn’t for a promotion obviously I would stay, but it’s just an opportunity at another building that was a good career opportunity for me.”

“The opportunity to work at a new high school is certainly appealing,” said computer teacher Megan Nyatawa. “The current principal there is someone that I worked with at Norris, and Buena Vista has a lot of computer science pathways, so they have five or six different pathways specifically focused on computer science. The one struggle at Central is teaching on the fourth floor, it’s hard to get to meet other teachers and experience the rest of the building. So it’ll be kind of nice to move to a school where I’ll introduce this school with everyone else and we’ll all build it and grow it together.”

For many educators, however, the decision to leave was not made in order to pursue career opportunities, but rather because of a feeling that continuing in their current positions at Central was untenable.

In the case of Latin teacher Brian Tyrey, his resignation was motivated by his own moral convictions. “Obviously, this wasn’t an easy decision. This was my dream job moving into education. In the last few years, I suppose I’ve been holding onto the hope that things are going to better and we’re going to get through this, and I’ve just seen that a lot of things haven’t been addressed that needed to be addressed,” he said. “We knew we were gonna have issues with staffing, there were some decisions made to make sure that we had enough teachers in the room with students to make sure all the classes are taught.”

In Tyrey’s situation, he was required to teach a Spanish class this year, a language he is not certified in. “If I did not choose to leave this year, I’m afraid I would be stuck with even more language classes that I’m not certified in, and I don’t think that’s the best benefit for the kids. It really comes down to morally I don’t think it is beneficial for me to be teaching students a language that I don’t know.”

Some educators spoke about the issues of mental health plaguing schools, feeling as if they lack the resources to adequately handle them in their current roles. “I would say that a part of teaching is supporting kids’ emotional-developmental needs and then another part is the academic-content-learning part,” said Molly McVay, who has taught social studies for five years. “And so there have certainly been other moments in my career where something terrible happened and there was a need to spend more time on the emotional and developmental aspects of students. Over the last two years, the amount of time that I have felt pulled to focus on the emotional needs of students as opposed to the content needs has really increased. And often, even when doing that, even when setting classroom time aside to do that, I still feel as though I’m not doing enough.”

Speaking on the rationale behind her departure from the school, she said, “I think [the pandemic] accelerated the rate at which I was critiquing the system. It shined a light in all the dark places both institutionally for the district and also in terms of my own growth and career visions. I have lots of peers who are friends whose jobs really shifted in a way that allowed them to feel safer during the pandemic and they have been slower to return to full-time work or their work-life balance has changed more positively and that didn’t happen for me.”

McVay also described the burnout she has experienced with engaging in the emotional work that teaching demands of her saying, “Whereas previously I might have been willing to take things home and continue to work at night that has become less and less true in the last two years because the amount of brainwork that I’m having to do during the day leaves me exhausted. It’s harder to leave students’ needs at home like I can separate ‘Oh, I should really grade that,’ that’s easy to do. But it’s much harder to recognize that students are feeling, uncared for or unloved or their home lives are terrible. Those are the things I think about at 2 a.m. when I’m not asleep.” McVay is planning to attend graduate school at UNO to get a degree in clinical mental health counseling and become an adolescent counselor.

Although he stressed his own departure is due to his weariness with his position, school counselor John Flemming also discussed his concerns with the mental health of students at Central. “Mental health is a big issue,” he said. “We just don’t have enough facilities to be able to help students that really need some help, and that’s made life much more complicated. What we really need is some kind of alternative school that will be able to work with the kids that don’t seem to fit in anywhere. I think what’s happened is some kids just aren’t fitting in and there’s nowhere for them to go, and they just have to stay here or at some other school. It’s not that they can’t do the work; it’s just like Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, you to have certain things provided to you to make education feasible.”

Some teachers felt that the pandemic had positively impacted schools in certain ways. “We’ve just been learning a lot,” said English Department Head Katherine Rude, who is leaving to be an 8th grade dean at Buffet Middle School after 17 years at Central. “I think that during COVID it was more important for the schools to be working more closely with the community to make sure all the supports were in place for all of our students and their families and the role of school really was highlighted. I think with absences and covering classes, there were some additional challenges, but we’ve kind of weathered those things and figured them out and we’ve gotten stronger.”

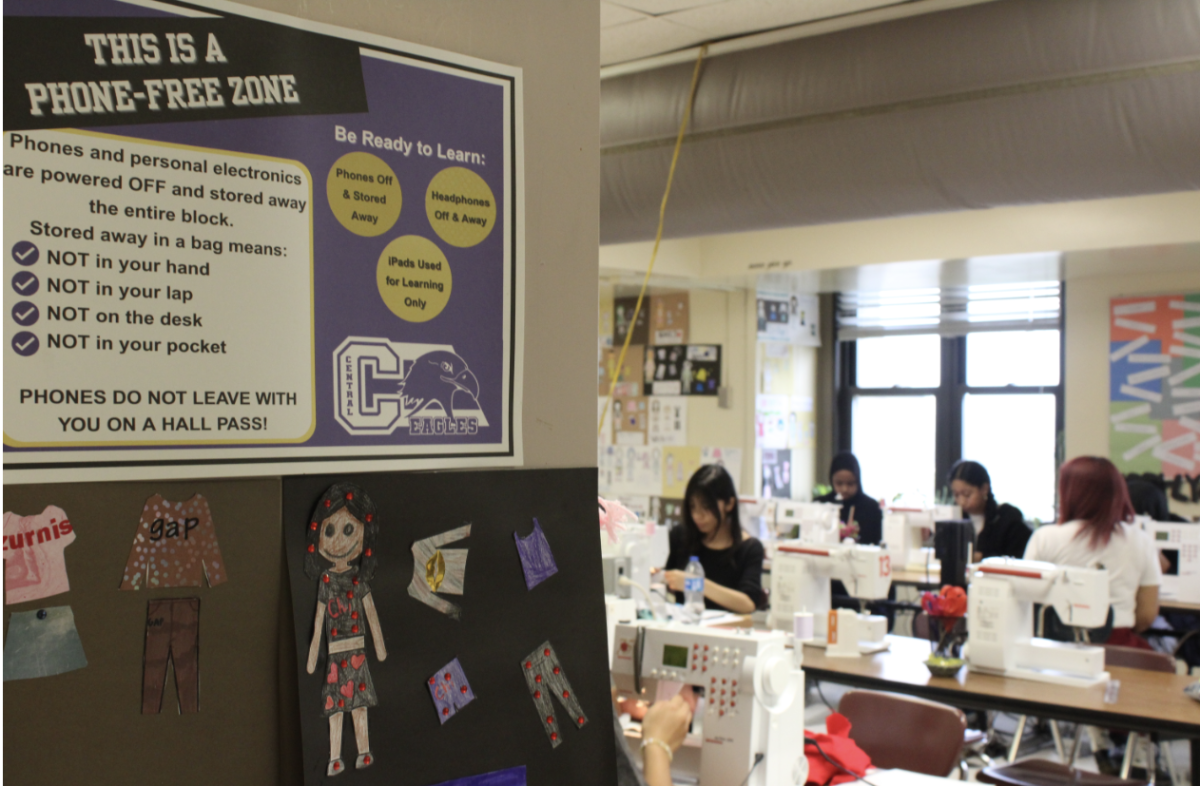

Others had a less optimistic view of the changes the pandemic brought to education. “The pandemic is an impetus for a lot of people who are leaving, because everything is just crazy,” said Reading teacher Aarron Schurevich, who is leaving Central after his first year at the school. “The fact that there are some students more enamored with phones than paying even a modicum of attention to what’s happening in class is utterly painful at times. It takes a lot of the emotional and intellectual energy out of the profession.”

“Clearly in the hallways, it’s out of control,” an anonymous teacher said on the rising misbehavior at Central. “You break up fights or you walk in the bathroom and kids are vaping or smoking pot. It’s not the end of the world but it takes away from the energy that you’re trying to give to your kids in the classroom.”

Other teachers themselves felt that their position did not allow them to maintain a healthy work-life balance. One such teacher is Cassie West, who has taught math at Central for 17 years. She said that her husband’s job requires him to work during afternoons and evenings, meaning he is frequently unavailable to help out after school. “With our kids getting more involved in activities, I realized two years ago that I probably needed to teach part-time in order to keep the balance.”

She applied to be part-time alongside her colleague Brianna Sommer, the plan being that she would work mornings while Sommer would work afternoons. In her initial email, West told OPS that she did not care if she stopped receiving benefits, if they stopped contributing to her retirement, and if her salary did not increase, her only request was that she be allowed to work part-time at Central.

It took less than an hour for a district administrator to email back and say that they were not considering part-time employment at this time. West was not told why they were not considering her offer. “I don’t know why they won’t,” West said. “I think that’s why it was harder for me to accept. I know my value and it was very frustrating to feel like they didn’t place any value on me.”

In addition to all the burnout she was experiencing and grappling with her family’s needs, she alluded to the demands being made of her to accommodate the new policies being implemented in OPS as being an impetus for leaving as well. “Some of the asks started to become too big. All the changes they’ve made in the last year, all the changes coming next year, it became too much,” she said. “It’s all the little straws and finally, one of the little straws breaks the camel’s back, right? It was November when I saw all those extra changes on top of everything else and I feel like I’ve bent and I’ve bent and I’ve bent and I finally broke.”

The sweeping changes coming to Central next year, in addition to the difficulties brought on by the pandemic, were referenced by some as a factor pushing teachers away from Central.

Among the teachers leaving for this reason is the Register’s adviser Hillary Blayney, who has accepted a position at Westside after leading the journalism program for 12 years and teaching at Central for 14. “I love my position here and what I do,” she said. “But with all the changes, with pathways and block scheduling, it’s really going to limit the amount of students who are able to take journalism, so I think a few years down the road the program won’t be as sustainable as it has been and that broke my heart.”

When pressed on who she believes is responsible for the rollout of all these changes to OPS, Blayney said, “I want to say pathways program was Cheryl Logan’s baby. I think it was a vision she had when she got hired and that Steele Dynamics was brought in and I hope it works out for OPS.”

The name of OPS’ current superintendent, who was hired in 2018, cropped up in some of the interviews the Register conducted. Most of the teachers who wished to remain anonymous cited fear of reprisals from Logan as the reason for their anonymity. “I was actually excited when they hired Cheryl Logan,” said an anonymous teacher. “I thought ‘This is a minority woman and a former Spanish teacher. Okay, this is someone who has been in the trenches. I’m excited, this could be really good’ and then it turned out she was just like every previous superintendent or even worse. It’s the same thing where it just seems like she isn’t here to effect positive change, we’re just a place for her to push her agenda and gloss up her stats.”

Elaborating on the effect that Logan has had on the work culture at OPS, the source said, “I just feel like she’s antagonistic towards teachers. It’s like if you are making a stand and pushing back, you are the enemy. When I saw it firsthand, I felt like teachers were pouring their hearts out saying what was happening. Instead of saying ‘that’s terrible, I’m sorry we’re going to work on it’ she was like ‘well, figure it out, that’s your problem’ and sort of just attacking teachers. As soon as anyone spoke out, she got really unprofessional.”

Echoing similar concerns about Logan’s conduct as superintendent, another anonymous educator said, “I think the lack of like professionalism is what bothered me. I mean to have all these people voice their concerns about pathways and block scheduling and what’s happening in our schools and her to just take it like it was something against her. I don’t know, I just think if you’re making half a million dollars a year leading a school district, you should be able to have meetings with your employees where you act professionally.”

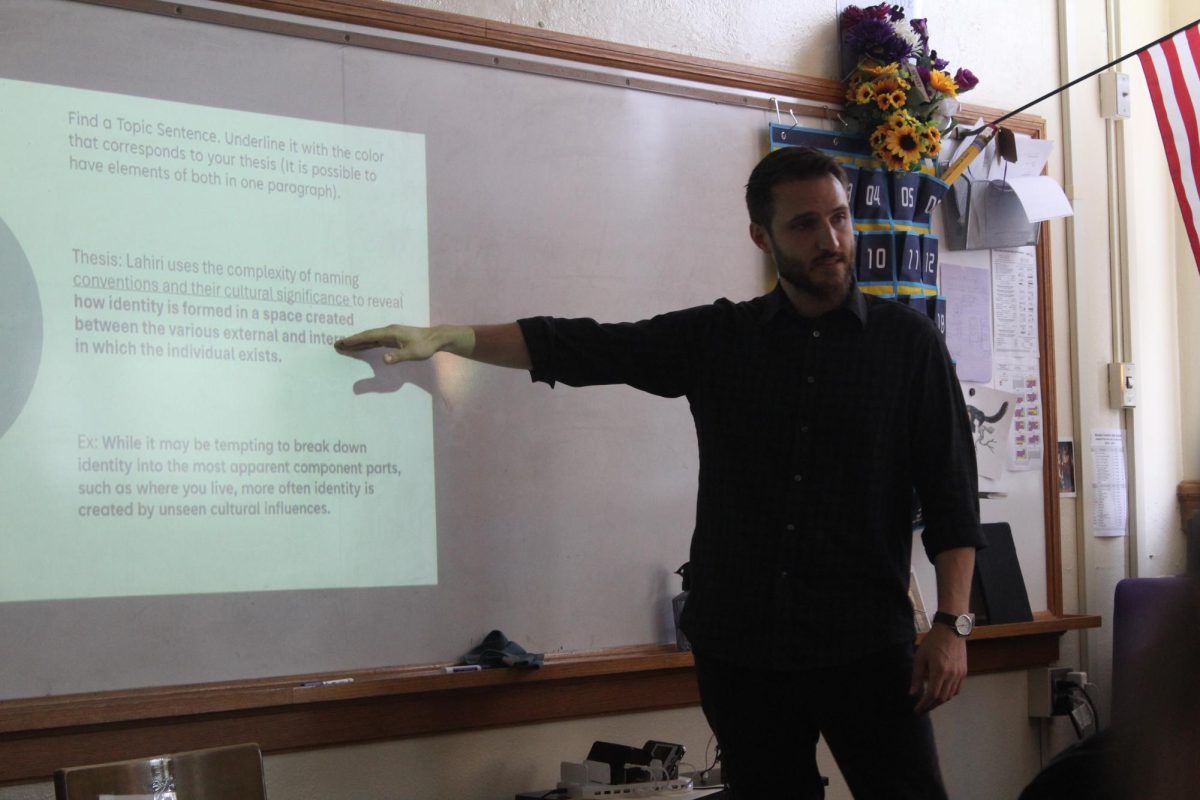

While some teachers listed their grievances with the current OPS administration, others discussed how the most pressing issue they see is how education is being affected by policymakers at a higher level. “I’m passionate about teaching and I care about my students. I like seeing the lightbulb go off in students’ heads, but there’s a moment where there are constraints placed on you that makes it difficult to pursue that passion.” Said History teacher Riley Overshire, who is leaving education altogether. “One thing in education that I have found to be difficult is the politicking in education. It’s a public job, it’s very much at the center of everything, and a lot of people have a lot to say about teachers that isn’t necessarily the truth and I don’t think that’s very fair. I just don’t see myself being willing to fight against something like that just to do my job.”

Schurevich shared how he thinks the culture surrounding education is harming public schools, saying, “You see this drive for labeling anything that displeases middle-aged white men as [Critical Race Theory] and the demonization of anyone who says anything about why bad things are happening to people of color and people who are poor. Ultimately, unless we have some big cultural changes and we stop trying to push all of our public school dollars into private schools or charter schools, I only see it getting worse. I mean my wife and I were talking about having a kid and then we were like ‘Wait a minute, are public schools gonna survive the next ten, fifteen years?’ and we’re not convinced they are and we’re both teachers, so we’re not having a kid anymore.”

The common thread that ran through almost all of the interviews the Register conducted was the last words of encouragement and gratitude that departing staff had for the teachers and students of Central. “I’m an alum as well so the building has always had a special place,” Tyree said. “This place has been a part of my life for over a decade, so I’ll miss the people.”

“I think this is a fantastic building,” Behrens echoed. “There are so many wonderful teachers and people that really are student-oriented, and that’s one of the great things about Central and that’s certainly something that I want to take with me to Westview.”

Speaking to the teachers at the school, West said, “I could not have done the last 17 years without them. This job would be too impossible without their support and their friendship and their humor and their laughter. And, I don’t know, it sounds silly, but forgive me for leaving. I hope that they can forgive me for leaving. They’re amazing educators and I feel really lucky to have been able to spend my teaching career with them.”

In his final words to educators, Schurevich said, “Sometimes teachers are too ready to accept what’s being handed to them. The fight is more important than acceptance when what’s on the line is existential. If it’s working conditions, if it’s leadership that’s not leading, sometimes sticking your head up and drawing the attention is worth the potential of suffering consequences. Going along to get along doesn’t benefit anyone except the people in power.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Omaha Central High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Hello Register readers! My name is Jane McGill, and this is my third and final year at The Register. I served as Executive Editor, editing The Register’s...

OPS Neophyte • May 9, 2022 at 1:55 pm

Interesting read. Some questions.

1. There is discussion of “changes”, but those aren’t discussed. It would be helpful if you elaborated on those for us who aren’t entrenched in schools.

2. There was talk of Cheryl Logan’s “agenda”. What is that?

3. Is this common throughout OPS? It would be interesting to see feedback from other schools.

4. I wasn’t clear why one of the teachers decided to not have a kid because they worry about public schools maybe not being around. Is he worried he won’t have a job or that there won’t be public schools for the child to eventually attend?

5. I’m glad the mention of politics made its way into this post, specifically calling out people obsessed with criticizing the CRT boogeyman (ahem, GOP candidates for governor). I’d really like to hear more about what is being taught vs. what conservatives are screeching in public.

Anna • May 9, 2022 at 10:29 am

Really phenomenal piece, excellent work!

Maddy • May 7, 2022 at 12:03 am

As a journalism student who works with block scheduling at their school it’s also been a struggle keeping students involved and the program has suffered for it. Loved the professionalism of the article and the wide range of viewpoints. Keep up the good work!

Bridget • May 6, 2022 at 2:29 pm

Extremely well written, with multiple perspectives shared. The national media needs to emulate this type of reporting.